What the Fish? - December 2019

A Brief Personal History of Man-made Fish

There’s no denying the fact that I’ve become a grumpy old fish keeper. In the four decades that I’ve been filling my life with fishes I’ve seen many changes to the hobby but consistently witnessed trends and fashions that seem to be a slap in the face to the natural beauty of what I consider to be the most diverse and interesting group of vertebrates on the planet.

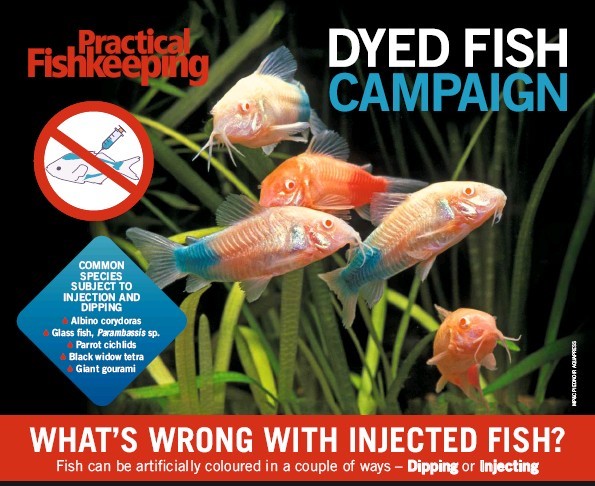

Let’s go back to a time when aquarium heaters didn’t have built-in thermostats, filters were mostly either boxes filled with filter wool & carbon or under-gravel plates and I had my first tank. Most pet shops selling tropical fish had tanks of amazing Glass perch (Parambassis sp.) with colourful fluorescent lines top and bottom, in a dazzling array of hues that would make an 80s pop video blush. Many of these ‘Disco fish’ would come down with a mystery illness that I’d come to know as Lymphocystis, the result of shared needles full of the dye injected into their flesh in order to increase the appeal of an otherwise drab borderline community fish. Thankfully this appalling practice has been universally condemned and we operate in a trade where such fishes are rarely seen.

Thousands of fishes came and went as time and progress marched on. Power filters became the norm and their electric motors silenced the loud bubbling of aquaria up and down the country as filters were no longer run by noisy air pumps. I had discovered cichlids, which is a lot like discovering girls for a young fish enthusiast but a lot easier to understand the hormonal conflicts and tendency towards aggression. Amongst the breathtaking array of species in all shapes and sizes, there appeared a very mysterious and odd-looking fish - the Blood Parrot. Developed by Asian breeders, experts of the time were flummoxed and some fairly whacky theories arose of the origins of these bright red, slightly wonky specimens that were clearly something to do with cichlids. “Fancy goldfish crossed with Severum” was one hypothesis I recall and nobody seemed to be able to afford or breed a group, outside the facilities of the farms that created them. “Must be hormone injected...” went another line of possibility, as the parent species of these distinctively-shaped fish couldn’t be recognised. A few of us were already slightly affronted that there was a rare and beautiful Amazonian cichlid that was the ‘True Parrot’ (Hoplarchus psittacus) even though very few of us had actually seen one in the flesh. A massive clue came in the form of a phone call to the aquarium shop I was working in at the time and I visited a customer that day who’s eyes were alive with pound signs as he showed me a tank full of fry with their parents - a Blood parrot and a Green Texas (Herichthys carpintis). When I was offered the fry for a mere £5,000 I thought of the words of investigative journalists everywhere and promptly made my excuses and left.

Possibly driven by the popularity of the parrots, the next wave of freaky fishes came in the inelegant shape of ‘balloon forms’ that share in common a congenital reduction in the number or form of vertebrae. With their short spines, they have a form more common to fancy goldfish and this brings an appeal to keepers who prefer their fish to look ‘cute’ and perhaps display a more quirky swimming style. Having bred a lot of fish over the years, it’s true to say that this trait appears in fry occasionally and like any domestic mutation, can be ‘fixed’ in a population through selective breeding. In the predator-free environment of an aquarium the swimming ability of our pets is less of an issue than it would be in the wild, meaning that these oddballs can enjoy a healthy life, having never known any different. It still grates a bit seeing an elegant classic such as a Pearl gourami (Trichopodus leeri) in this cartoonish form but it’s not really hurting anyone, or replacing the unadulterated wild form.

In laboratories in various parts of the world, experiments were being undertaken to help in the detection of aquatic pollution and cancer. One of the tools developed to aid science were transgenic fish, which had their genes altered to incorporate those of jellyfishes. Far from the Jurassic Park rampage that Hollywood had promised us, these fish were quietly turning fluorescent pink, yellow or other bright colours in the presence of aquatic pollutants hazardous to human health, or developing Day-Glo tumours in cancer investigations. It was only a matter of time before someone noticed their aquarium application and the next stir on the market was caused by bright pink danios that glowed like corals under deep blue light. Many of us had instant knee jerk flashbacks to the dyed disco fish of the past when confronted with these fish and baffled breeders assured us that they were produced like normal danios and no artificial processes were used. They were right of course, the fish passes on the altered genes and no harm is done to them, unlike the colour injected or dip-dyed individuals of other species such as parrots (them again!) that are ironically not banned for sale within the EU by the laws on transgenic livestock. If you’re curious, search for ‘Glofish’ and you’ll find a thriving trade in the US for trademarked animals who’s production rights are held by a corporation. It sounds like a plot that involves a bit of rampaging by engineered creatures but so far nobody’s been decapitated by an enraged danio or widow tetra. One lives in hope..

A flutter of excitement greeted the appearance of the new and interesting Electric Blue Jack Dempsey (Rocio octofasciata) that the stories say was bred in the fish house of an Argentine aquarist. This bright blue bundle of recessive genes does have some traits I’d associate with a hybrid but details of their origin are sketchy. From the outset, these fish have always had strange body and fin shapes compared to their wild type relatives and they certainly lack the vigour that saw them named after a renowned boxer. For those seeking a blue cichlid for a large community, the Electric blue acara (Andinoacara pulcher) is probably a better choice and is as hale and hearty as the normal form.

It seems that there’s a pattern emerging of hybridisation and alteration of natural body types, so the stage was well and truly set for the latest of the ‘frankenfish’ to shake the hobby in the raging unit of a fish that is the Flowerhorn cichlid. As we’ve seen, parrots were hybrids with a peculiar quirk of being fertile when crossed with related species. It’s actually the females that are fertile it seems and this group of fish are far from fussy - I’ve often joked that you could breed a Convict (Amatitlania nigrofasciata) with a tuna sandwich if you could stop it getting soggy. This potential meant a range of awesome and psychotic Central American cichlids could be used to make a weapons-grade parrot; one that displayed the proud nuchal hump of a warrior and the awesome power of species that were extremely rare outside the fish houses of dedicated masochistic enthusiasts.

Shaped by the aesthetics of Asian keepers, the Flowerhorn was born. The pursuit of these fish would forever muddy the water for those cichlid keepers who found themselves faced with potential hybrids that looked like one of their parent species and the quest to find unrelated breeding stock was now tied to seeking other purists who kept their pets catalogued and free from interaction with spawning partners of unknown origin. Those keepers who simply wanted an interactive pet fish that was fearless and sparky found they could now buy their dream fish. Love them or hate them, these cichlids raise very interesting questions about the definition of species and have the potential to bring about a renaissance in the popularity of their pure cousins.

I’d love to say a lot has changed since those disco fish days but sadly there are still dyed fishes appearing for sale, together with those that have been tattooed or surgically altered through the removal of tails at an early age. These are the artificial fishes that should make us all angry, whether we’re purists or not.

This brief history of unnatural fishes in the hobby is really nothing new. Ever since Chinese breeders started tinkering with goldfish over a thousand years ago, we’ve been altering the appearance of pet fish to suit our tastes. Many of the fish you’ll see in aquaria worldwide don’t exist in the wild and a surprisingly high number of them from platies to angelfish and discus, are hybrids. Even some of the species prized by specialists are aquarium forms that have been line bred to enhance their natural colours or finnage. Ever since that first red goldfish appeared, we’ve been changing things and if you enjoy keeping these gaudy specimens you’re observing a fine tradition of aquarium keeping.

For those of us who own a tiny glass shrine to the wilder world of fishes as they appear in nature, there’s never been a better time to be a fish keeper. As long as wild habitats remain intact there’s an inexhaustible supply of mysterious Corydoras catfish to identify, sublime tetras that lack scientific names and dwarf cichlids that demand the concerted efforts of the faithful to transform them into subtly beautiful legends of the leaf litter. Find the fishes that make your heart beat faster and dive in.